Writing and Research

2024

Dissertation

An exploration of the ways that women might disengage with misogynistic forms of thought and language and reconnect with their bodies as a route out patriarchy.

Table of Contents

Concept as new ways of thought

Language and women’s embodied writing

Conclusion

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Introduction

In a commencement address given to Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, USA, the author Ursula Le Guin introduces the idea of Mother Tongue and Father Tongue. She explains that Father Tongue is the language of science, academia, politics and power. It is also the language of objectivity, separation and distance; it is the language of the rational, of speaking down, of lecturing, of no questioning and of being right. It is the language we come to learn at university even if our chosen subject is Art, Architecture or Archaeology. Mother Tongue on the other hand is the language we are taught from birth and the one we must later reject, if we want to appear reasonable, rational and educated. It is the language of connection and conversation; the language of subjectivity, experience, repetition, of waiting, of not-knowing. It is non-linear and non-hierarchical. (Le Guin, 1989). I mention these concepts in the introduction because I would like to include some Mother Tongue in this essay and to question whether this expansive nuanced language, that doesn’t claim to know the end from the beginning, may be an entry point into new ways of thought and being. Rather than looking to create a promised utopia – someone’s idea of a perfect civilisation in an unreachable ‘no place’ – Mother Tongue may be the way to access a real place in the here and now, a utopia that begins internally and is accessed by feeling; a place that is created by small decisions to think and act and be the way of difference. Perhaps, as Emma Dabiri says in Disobedient Bodies it is a way of refusal to what is and what has been (Dabiri, 2023).

This essay will begin with a well-documented reminder of what has been and where we are in terms of the patriarchal systems that govern our society and most of our world. It looks at statistics relating to violence and rape as a reminder of how far we haven’t come, particularly when thinking about phrases like ‘post feminism’ implying that all feminist goals have now been reached.

I will touch on some of the philosophical theory that is foundational to much of patriarchal thinking but is not always voiced in populist discussions of the subject. I will then move onto ideas about thought, about how we think in light of Deleuze’s statement that thought needs a revolution much like the move of realistic art into abstraction; and Elizabeth Grosz’s ideas on the Future of Feminist Theory and Freedom. I will mention ideas of flat ontology and new materialism as opportunities to break out of Anthropocentric thinking and consider whether, within this arena of alternative ways of thought, there is a space for allowing the unknown as an opening for the new; a space to move from our minds into our bodies and ask questions about how art is able to facilitate that process. And finally, how re-inhabiting our bodies as sites of knowledge and wisdom might help us to find our true home and, once found within, might enable us to create it on the outside.

I am aware that I have taken a strong binary position in this essay and have deliberately chosen to do so because I suspect that some of the polarity and intensity that occurs in current gendered debates is rooted in the issue of violence against women which has not been resolved adequately enough to allow for more nuanced and compassionate discussions on both sides. Male violence against women in sadly binary in the extreme. I may be wrong or behind the times in doing this but refer to a quote in Lauren Elkin’s latest book, Art Monster: Unruly. Bodies in Feminist Art, where she states that, “feminists sometimes get it dreadfully wrong or ecstatically right or both at the same time. That the best of feminism is a movement that makes room for the at the same times, for the I don’t know what I’m looking ats, for glorious ambiguity – that claims its space” (Elkin, 2023:22). I hope to do all the above.

Violence Against Women

A much more basic questions contained within my essay title is, ‘Why is equality for women taking so long?’ and this question is embedded in the issue of violence against women. In an article on the VOICE website, feminists and activists Heather Cole and Anu Pillay list some of the work feminists have done to progress this issue:

“[They have] generated the data, made presentations, written reports, marched, argued, proposed policy changes, demanded change, convened, tracked the resourcing, built the skills… built services, often voluntarily, for survivors, developed service standards, designed prevention programs, pushed to strengthen protective mechanisms… brought the language to describe survivor experiences, name the realities of being women and girls in patriarchal worlds.”

But they point out:

“So little has changed. Every time we have a surge of activism… we hear the same resistances: we need to educate boys and start with the next generation; it will be different at some unspecified point in the future; it’s not that bad; women and girls exaggerate; there’s so many false accusations because women and girls have regrets after bad decisions; they provoked it; they were engaged in risky behaviours; they were drunk, or drugged and careless; they shouldn’t have been out; they shouldn’t have married him; they should have called for help […]

“When we challenge these tired old tropes, we meet another layer of resistances: you need to bring men on-side; you need to be less aggressive; you need to stop making such a big deal about it; Not All Men Are Like That; is it really that big an issue, though, compared to every other issue we could be talking about?; you have to stop blaming men; it’s awful but those men are different and it’s sad but we really don’t see what it has to do with us” (Cole & Pillay, 2021).

In specific terms of violence against women, things don’t seem to have moved on from the 1980’s. In Sexual Politics, first published in 1971, Kate Millett comments that “the military, industry, technology, universities, science, political office and finance – in short, every avenue of power within the society, including the coercive force of the police – is entirely in male hands” (Millet, 2000 :24). One could add the judicial system, especially thinking of Roe v Wade, and while women have made inroads to these pockets of ultimate power and control, there has been no significant change. While discourse in feminist theory expounds these issues, sometimes the facts simply speak for themselves:

-

Women aged 15-44 are more at risk from rape and domestic violence than from cancer, motor accidents, war and malaria.

-

At least one in three women around the world have been beaten, coerced into sex or abused in their lifetime.

-

If violence against women were a disease, it would be referred to as an epidemic.

-

603 million women live in countries where domestic violence is not considered a crime.

-

Half of all women who die from homicide are killed by their current or former husband or partner.

-

Between 1.5 million and 3 million girls and women die each year because of gender-based violence.

(unwomen.org, s.d)

Rape As Reality

The VOICE website, previously mentioned, ran a series of webinars which “brought together women and girls from around the world to discuss what it would be like if we had one day, just 24 hours, without sexual assault” (Cole & Pillay, 2021). This was based around a speech given by Andrea Dworkin to a group of 500 men from the Men’s Movement in 1983. It clearly conveys the unseen, often unspoken, sometimes unaware, reality of women’s lives:

“We do not have time. We women. We don’t have forever. Some of us don’t have another week or another day to take time for you to discuss whatever it is that will enable you to go out into those streets and do something. We are very close to death. All women are. And we are very close to rape and we are very close to beating. And we are inside a system of humiliation from which there is no escape for us” (Dworkin 1983, cited in, MITPress, 2019).

In 1977, Suzanne Lacy’s performance piece 3 Weeks in May created some sense of this lived reality for women at a time when rape was rarely talked about and certainly never mentioned by women. She included, amongst other things, a map showing where rapes happened in LA during a three-week period. She contacted the police department daily to get accounts of reported rapes and then marked them on a map which she displayed outside in the open rather than within a gallery.

Fig 1 Three Weeks in May (1977) Fig 2 Three Weeks in May (1977)

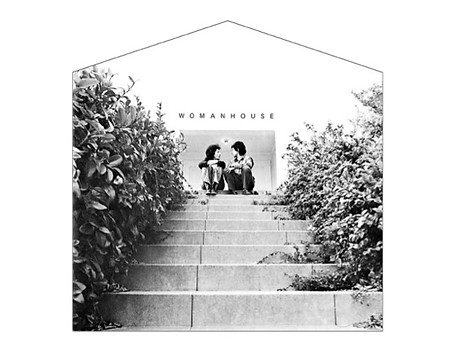

Earlier in that decade, Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro presented a month-long exhibition called Womanhouse which was the first public exhibition of art centred upon female empowerment. Chicago, Shapiro and students from the Chicago’s California Institute of the Arts Feminist Art Program transformed a dilapidated house into an installation and performance space using materials and language which, at the time, were not considered suitable for artistic expression, as Lippard recognized: “The prime taboo in the early seventies was lived female experience and ‘feminine’ materials used in unexpectedly perverse ways and contexts.” (Lippard, 1995:22)

Installations included Nurturant Kitchen, in which the walls of a kitchen were covered in fake fried eggs that morphed into breasts, a laundry cupboard containing a mannequin constrained at the neck, chest and torso by shelves and Menstruation Bathroom which was filled with a variety of menstrual items including a bin overflowing with bloody pads and tampons.

Fig 3. Womanhouse (1972) Fig 4. Menstruation Bathroom (1972)

In a documentary film of the event, Johanna Demetrakas’ includes a performance by one of the artists who describes a night out that starts off filled with all the joy and exuberance of 70’s hippy culture, with peace, love and a little bit of acid. It has the audience laughing and enjoying the characterisation but as she skilfully moves into a description of rape remembered through the veil of LSD, the audience becomes silent and completely still. It was mesmerising and captured the way in which women have to question external reality, their sanity and the validity of their own experience (Womanhouse, 1972).

In a more recent one-woman play, called Prima Facie, Jodie Comer plays a lawyer who specialises in defending men accused of sexual assault, until she is assaulted herself. The second half of the play harrowingly describes how, even a lawyer with all the knowledge of the legal and court system, is unable to gain a conviction, highlighting just how the law fails to protect women.

As we consider this ongoing reality of violence and rape, it is hard to argue with Australian philosopher and feminist theorist Elizabeth Grosz who comments that “feminism has not succeeded in either of its competing and contradictory aims; either the creation of a genuine and thorough-going equality… or the constitution of a genuine and practical autonomy.” (Grosz, 2011: 75).

What You Resist Persists

Of course, feminism has made profound changes. The protesting, demonstrating, petitioning and sacrifices made by hundreds of thousands of women over the last century has succeeded in getting women the vote and opening doors into the workplace and onto the career ladder. It has also gone some way to reducing the pay-gap and it did win abortion rights (for a time!) But perhaps as Sonia Johnson states in Going Out of Our Minds (1987) this form of ‘pushing against’ only invites a pushing back. Controversially, she would say that ‘fighting against’ is a form of collusion: putting energy into what you don’t want is still putting your energy into what you don’t want! Is there any energy left, physically, emotionally and creatively to put into what you do?

Johnson is not a household name in the world of feminist theory, which is surprising as she was part of the leadership of NOW, campaigned tirelessly for the ratification of the ERA, including a forty-nine day fast and in 1984 ran for president on a purely feminist agenda, finishing in fifth place. She appeared to be a step ahead of her feminist peers which often meant she was slightly out of favour. She went down the road of civil disobedience when others in the movement felt protesting was a better option. Her lengthy fast brought disapproval from many feminists who felt she was diminishing herself and her campaign for president met with disagreement because many felt she would be diluting the votes for the pro-women male candidate who had more chance of succeeding. Most controversially perhaps, she came to a realisation of the pointlessness of all of the above, gave it all up and spent the latter years of her life working with groups of women to imagine a new future. Her belief was firmly that what you ‘resist persists’ and she actively withdrew her energies from all those areas (Johnson, 1987). Fighting against what you don’t want is very different from imagining what you do.

To some extent, the changes that feminism has fought so hard for – and in some cases won – have all been done within the patriarchal model. Women have tried to make change patriarchally – protest, violence, civil disobedience, fasting, in parliament, in the workplace, in medicine. Every move forward has been ‘approved’ and ‘permitted’ by patriarchy itself and been guided by the expectations and norms set down by that system and its structures. As Audre Lorde saw so clearly, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” (Lorde, 2018).

Hannah Stark suggests that it may be time for women to “redefine themselves and devise realistic scenarios for altering the present and constructing the future”. In Feminist Theory After Deleuze (2016), she points out that this cannot be limited to the “material and ‘realistic’ conditions of women under patriarchy. Feminist theory also needs to find a speculative register, new ways to think, create, live” (Stark, 2016:2). In other words, we need to move out of our current reality ‘mentally’ before we can do it physically, and need to draw on more fluid and less fixed ideas of what the future could be.

The Nature of Reality

Sonia Johnson and Elizabeth Grosz discuss the systemic nature of reality in different ways; one might say Mother Tongue and Father Tongue. Johnson writes more experientially and biographically using the language of intuition or internal knowing and Grosz from the viewpoint of an academic theorist. It is interesting to get a sense of the commonality in what they are both trying to say.

Johnson began a talk she gave in the late 1980’s by questioning the nature of reality. Using the metaphorical story of Magellen arriving in newly discovered lands with ships that were invisible to the indigenous people (because they simply couldn’t conceive that such large ships existed) she suggests that reality is what we expect to see; it’s what we pay attention to, what we engage with as real. Reality resides first within us – ‘all systems are internal systems’ – and we then project them externally, institutionalising and making them objective. If we stop projecting our belief in patriarchy, stop interacting with it, it stops existing (Going Farther Out of Our Minds Part 1, 2016).

This idea is not dissimilar from a view that Grosz expresses when discussing dominant areas of feminist theory that she would like to see moved aside to allow new questions to be asked. She suggests that “the notion [of] various forms or types of oppression [as being] recognizable, systematic and distinct (if overlapping) structures needs to be reconsidered” (Grosz 2010b:51). She questions how helpful it is to view patriarchy (or racism, classism or ethnocentrism) as fixed structures or systems and whether it is more useful to recognize them as a “myriad of acts, large and small, individual and collective, private and public.” She clarifies that she is not saying that these oppressions do not exist but that they “are not structures, not systems, but immanent patterns, models we impose on this plethora of acts to create some order” (Grosz, 2011:51).

In Hope in the Dark, Rebecca Solnit gives a comparable example when she suggests that although we live in a capitalist society most of our everyday lives, our relationships and our “memberships in social, spiritual and political organisations are in essence non-capitalist […] full of things we do for free, out of love and on principle” (Solnit, 2016:xv).

I think this way of breaking down the concretised view of our current systems, whether patriarchy or capitalism, is very helpful in dissolving the idea that feminism must destroy one system and have a ready-made replacement at the exact same time. Removing the requirement of a ready-to-go utopia waiting to be implemented opens up the “spaciousness of uncertainty” which Solnit sees as the location of all hope (Solnit, 2016:x11).

The Part Philosophy Plays

In a previous essay, I discussed the political and economic conditions that required women’s unpaid labour to sustain them and here I want to look at the philosophical theories that undergird and maintain women’s ongoing inequality and permit, if not create, opportunities for violence.

Stark summarises the historical theories that position women as less-than-human, alongside anyone and anything that is not white, male, middle class etc. She begins with the Enlightenment and the Cartesian philosophy that separates the mind from the body, elevating the mind and linking it with the masculine and devaluing the body and linking it with feminine. This philosophical dualism offers a “constructed system of values”. Man is valued and is aligned with “the mind, reason, rationality, culture and the position of the subject.” Woman is the opposite sitting on the devalued side “aligned with the body, passion, irrationality, nature and the position of object.” She explains that “this hierarchy contributes to a gendering of reason and rationality and the masculine. Because rationality is an attribute that has designated the human, the exclusion of women from thought also marginalises them in relation to this category” (Stark, 2016:3). Genevieve Lloyd suggests that the maleness of reason goes deeper than dualistic classification and is, in fact, an expression of value and what is valued most highly is essentially male. (Lloyd, 1993:104)

In Sexual Politics, Kate Millet discusses the idea of the ‘norm’ being exclusively male, “in patriarchy, the function of norm is unthinkingly delegated to the male - were it not, one might as plausibly speak of “feminine” behaviour as active, and “masculine” behaviour as hyperactive or hyperaggressive” (Millet, 1990:7.)

Carol Gilligan expresses this idea through the lens of psychological processes and theory and questions the particular ‘theories in which men’s experience stands for all of human experience – theories which eclipse the lives of women and shut out women’s voices” (Gilligan, 1993 p. xiii).

The art historian and writer Marina Warner introduces the idea of women’s lack of subjectivity and their becoming subject matter in men’s art and makes particular reference to statues. She says “Statues of men are usually a person, a historical or sometimes mythical person. Whereas the women depicted were not active in the world they were usually personifications; they were abstract ideas like liberty and justice. In London you have Justice on the old Bailey and Nelson on his column. Justice is not a person, not a judge, not a woman wielding justice, she’s an abstract idea. She is subject to the maker’s imposition of meaning; she is not allowed to speak for herself.” (Warner, 2023)

Rebecca Solnit describes her lived experience of these biases by proffering her opinions and “finding that some of the people out there, particularly men, respond on the grounds that my opinion is wrong, while theirs is right because they are convinced that their opinion is a fact, while mine is a delusion” (2017 p.157). She goes onto say with ironic humour that “it is a fact universally acknowledged that a woman in possession of an opinion must be in want of a correction. It isn’t a fact universally acknowledged that a person who mistakes his opinions for facts may also mistake himself for God” (Solnit, 2017 p.157).

Clarifying the latent misogyny in these submerged yet fundamental belief systems upon which society and culture is built may help to explain why the one hundred plus years of extreme feminist effort has not been able to achieve the equality it so desires. As Lloyd points out “Women cannot easily be accommodated into a cultural ideal which has defined itself in opposition to the feminine” (Lloyd, 1993:105).

Although I am highlighting the male/female binary, I don’t necessarily believe that the problem lies therein. The issue is not that there are men and women and they are different, the issue is the value placed upon each side. In her essay, ‘Sexual Difference and the Problem of Essentialism’ (1995), Grosz points out that sexual difference will not go away. It may develop, expand and change but in some ways the simple problem is how the two sexes can live together in a way that satisfies both.

Dissolving the binary position will not dispel the underlying deep-rooted beliefs; however, stretching, softening and merging the boundaries may help to improve the situation. The heart of the issue, for me, is how we view and interact with this reality, how we relate to each other and the world. Replacing or re-arranging the labels isn’t enough. We need new thought, new ideas, new ways of being

.

Who Creates Reality?

In a 1998 essay, the scientist Ruth Hubbard, who was the first woman to have a tenure in Biology at Harvard University, discusses the reality of facts and I am extrapolating those ideas to question who is allowed to ‘make’ reality and what social or group characteristics are required to do so. She demonstrates how the systems I discussed earlier come to be objective realities. She describes how within the world of science, ‘facts’ come to be objective through the process of being submitted to the scientific community, reviewed by colleagues and shared with qualified strangers. If that all goes to plan, a person may become an accredited fact maker and their facts “come to be accepted on faith and large numbers of people believe them even though they are in no position to say whether what are put out are facts rather than fiction” (Hubbard 1988). She notes that women’s research and experimentation in the home is not dissimilar to the learning that comes from scientific experiments, but this is never deemed credible or important. In response, she lists the ways in which education, academic training and socialisation result in thinking in a certain way, being familiar with a ‘narrow slice’ of human history and culture, and not deviating too far from accepted rules (Hubbard 1988). Hubbard limits her questioning to the scientific world, but Grosz discusses a similar idea within the social sciences and looks at how agreed truth becomes power, proposing that truth is the victorious form of knowledge, and that truth becomes a fixation that everyone has to believe in order to get funding! (FTW 2009 Elizabeth Grosz, 2010).

Dan Bruigger includes the art world when he discusses what an artist must do in order to have an artwork recognized. “They must build deliberately on the past, with liberal references to other works as landmarks, in order to situate [the artwork] in a legitimizing tradition This aspect of the art world resembles academia, where scholarship is commentary on the commentaries of others, in a language that identifies one as a member of the profession” (Bruiger, 2019).

These arguments could be extrapolated to philosophy, politics, law, in fact all the pockets of power mentioned by Millett. Peer review is an incredibly efficient way of ensuring certain groups of likeminded people are able to maintain their position as gatekeepers of knowledge and power.

It seems a perfectly reasonable reaction when faced with this type of exclusion to want to seek inclusion, but as Stark states: “The question raised with the concept of reason is: should we claim that women must be granted access to rationality as it currently stands, or do we need to change how we think about thought itself?” (Stark, 2016:17).

Concepts As New Ways Of Thought

The Philosopher Giles Deleuze suggested that thought needed to go through a revolution in the way realistic art moved to abstraction. In opposition to Descartes model of the ‘cogito’, he disconnects thought from the subject, and “theorizes it as a creative and involuntary action that is immanent in the world”. (Stark, 2016:20) This simple act of removing thought from the person, the ‘I’, and putting it out into the world as an independent entity offers a revolutionary democratization of thought and thinking; it removes the binary divisiveness of the gendering of thought and rationality without engaging with arguments on either side.

Grosz develops this idea of new ways of thinking about thought when introducing ‘concepts’ in her essay titled, ‘The Future of Feminist Theory’. She discusses the failure of feminism to create true equality or a practical autonomy “in which women choose for themselves how to define both themselves and their world” (Grosz, 2011:39). She suggests that instead of trying to predict what feminist theory will be, we should be asking “the much less depressing question of what it could be?” (Grosz, 2011:39). She inquires, “How can we produce knowledges, techniques, methods, practices that bring out the best in ourselves… that open us up to the embrace of an unknown and opened future, that bring into existence new kinds of beings, new kinds of subjects and new relations to objects” (Grosz, 2011). For Grosz, feminist theory ‘at its best’ is about the generation of new thought and new concepts. She introduces Deleuze and Guattari’s idea of ‘concepts’ as a way of dealing with chaos. Concepts are ways of dealing with problems generated from outside. They are not solutions but “ways of living with the problem … they enable us to surround ourselves with possibilities for being otherwise” (Grosz, 2011). She goes on to say that “we tend to think that solutions eliminate problems when in fact the problem always coexists with the solution” (Grosz, 2011). While I can’t imagine Sonia Johnson ever using a phrase like ‘co-existing with the patriarchy’, she certainly gave up the notion of fighting against it.

This idea of concepts as providing us with ‘possibilities to be otherwise’ opens up a whole new way of thinking about living with the current system while imagining, exploring and creating the new and removing the need for that ready-made alternative.

This language or this way of thinking is much more Mother Tongue, much less fixed, less either/or. It resonates with a Buddhist way of thinking around notions of being open or closed, concrete and fixed or having some flexibility and space. Grosz’s suggestion has a sense of space around it; there is room to move, other options to consider than simply the destruction of the patriarchy. In fact, in the same essay, she goes on to say that “concepts carve out for us a space and time in which we may become what we can respond to” (Grosz, 2011:43); which seems to me a beautifully non-combative and revolutionary way to address the issues of patriarchal violence. She adds, “concepts are thus ways of addressing the future and, in a sense, are the conditions under which a future different from the present – the goal of every radical politics – becomes possible” (Grosz, 2011:43).

Freedom From, Freedom To

In a chapter in New Materialism, Grosz develops this idea in her discussion of freedom, expounding the difference between freedom ‘from’ and freedom ‘to’. One could say that much of the feminist struggle has been to achieve a freedom from patriarchy, a freedom from oppression, violence and the limits that it has placed upon women. Grosz introduces the idea of “a positive understanding of freedom as the capacity for action” (Grosz, 2010:140). She questions which option best serves feminist theory (and women themselves): a freedom that relies on emancipation from constraint by another or one that explores what women in and of themselves are capable of making or doing. She explains how the negative view of freedom is tied to the “options or alternatives provided by the present and its prevailing and admittedly limiting forces” and implies that once these limiting forces have been removed “a natural or given autonomy is somehow preserved”. In other words, once patriarchy has been dismantled, women will be free and autonomous to enact their freedom. (Grosz, 2010:141)

This raises an interesting point about how or whether it would be possible, after centuries of undermining, violence and oppression, for women to be truly autonomous. The discussion has focussed more on how women want the world to be or not be, rather than who we might be in that world.

In Loving to Survive, Dee Graham (1994:xiv) states that “No-one has any idea what women’s psychology under conditions of safety and freedom would be like.” Her research resulted in ‘Societal Stockholm theory’, which proposes that “women’s current psychology is actually a psychology of women under conditions of captivity – that is conditions of terror caused by male violence against women”. [1] She looks at the patriarchal system as a form of Stockholm syndrome. That the result of thousands of years of patriarchy has resulted in women colluding in their own oppression because they are unable to see beyond the system that has imprisoned and gaslit them for so long.

Graham is putting forward the idea that “women’s responses to men and to male violence, resemble the response of hostages to their captors” (Graham 1994: xiv). She suggests that in the same way captors need to kill or wound a few hostages in order to achieve their goal, the violence that women experience, or watch, or read or hear about is ensuring patriarchy achieves its goal: “women’s continued sexual, emotional, domestic, and reproductive services” (Graham, 199:xiv). Although extreme in some sense, it does provide a reasonable explanation as to why violence against women seems to continue with no deterrent great enough to eradicate it.

Graham’s Societal Stockholm theory highlights the potential difficulties for women to claim the freedom that Grosz is talking about. However, Grosz offers some helpful insight. She references Henri Bergson’s conception of freedom which is not dissimilar to Deleuze’s ideas of separating thought from the subject. Bergson does not think of subjects as free or not free but brings focus to the ‘act’ which he says has the ‘qualitative character of free acts.’ Free acts are the result of the subject alone and not the result of “any manipulated behaviour around the subject” (Grosz, 2010a:144). He believes acts are free when they: “spring from our whole personality, when they express it, when they have that definable resemblance to it which one sometimes find between the artist and his work” (Grosz, 2010a:144).

Free acts have the potential to transform the person doing them. The ‘doing’ is part of the transformation, they have ability to both express us and change us.

This theoretical position was enacted by first-wave feminists in the 1970’s and in Johnson’s work in the 1980’s. Susan Griffin talks about the internal revolutions that took place when women began to tell their stories, share their experiences of rape, acknowledge their realties. She states that “[T]hese small changes in the doing of things were in themselves a feat. And they do herald more to come. Because the making of these small changes changed us. And these changes inside us were not small; we were profoundly different now than we had been before (Griffin, 1986:42). Those changes were free acts and those free acts went on to enable the setting up of women’s shelters etc. Once Johnson had given up her activism in the form of civil protest or non-violent action she began to form women’s groups that envisioned the kind of world women might want, how it would feel it live in a world where women were free and equal and safe. She was clear that imagining the future in some powerful way caused change and that the key was in beginning to live those changes in the present. She believed that the “means are the end” and “how we are now is the future” (Johnson, 1987:295). In Hope in the Dark, Solnit quotes Paul Goodman, who was thinking along the same lines, “Suppose you had the revolution you are talking and dreaming about. Suppose your side had won, and you had the kind of society that you wanted. How would you live, you personally, in that society: Start living that way now” (Solnit, 2015:xxii).

Space For Not Knowing

But how do we begin? What can we do in the space and time that concepts could carve out for us? Perhaps as an antithesis to the overvalued reason and rationality, there needs to be a space for not knowing. As Solnit (2016:16) says, “Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable”, it provides an alternative to the perceived certainties of our lived realities. It is therefore a difficult space to enter and reside in, but if we can, it provides us with a pause, an allowing for something as yet unknown, as yet unthought, as yet unarticulated. A groundless space. Perhaps art offers an entry point into such a space both for maker and viewer. In her essay Tactics for Not Knowing, Emma Cocker explains how our early experience of establishing ourselves as beings in the world requires moving from "what is not known into what can be named and classified. The blurry and indeterminate realm of flows and forces in which we spend our early days is swiftly brought into line, once words are taught to differentiate one thing from another, the self from everything else” (Cocker, 2013:126). As we go through school, we discover that “to not know is treated as a deficiency or failure, as a mark of stupidity, the lack of requisite knowledge” (cocker, 2013:126). And we learn that the only space in which not-knowing is acceptable is the allocated timeslots called ‘play.’ So, it is understandable that to give not knowing worth and value is something of a cultural challenge. But as some of that culture is exactly what needs to be challenged is, it seems to me, a worthy pursuit.

Artistic practice at its most basic is making an idea reality, bringing something that was once only a thought, idea or concept from an unknown realm into the real world. Mixing the intangible with the tangible, putting form to what was formless contains an alchemy that is sometimes lost the minute we try to put words to it. As Cocker describes “the tongue shapes words all too quickly, and once named, edges reappear. (Cocker, 2013:128)

The cognitive archaeologist Lambros Malafouris (2013:95) discusses the non-discursive nature of ‘things’ themselves. He says, ”Things act most powerfully at the non-discursive level, incorporating qualities (such as colour, texture, and smell) that affect human cognition in ways that are rarely explicitly conceptualized. These are properties not afforded by the nature of the linguistic sign. The distinctive properties of the material world bring about meaning in ways that language cannot.“

As artists we are also gifted to explore the knowledges hidden within materiality. With our hands we have the chance to engage, converse and respond with and to materials that have no audible voice. As society begins to accept the devastating consequences of an Anthropocentric worldview, we have a choice. We can continue to embrace infinite reconfigurations of our current knowledge to provide ever-increasing forms of growth and information. Or we could choose to expand our capacity to relate in new ways to the materiality present in the world around us, thereby finding new kinds of knowledge that may not result in capital growth or profit but may bring improvement to our lives and the planet in wholly different and unexpected ways.

New Materialism

New materialism and ideas around vibrant matter stand in complete contrast to the Anthropocentric worldview and offer an opportunity to pause and re-consider what we have been so certain of in the past. Jane Bennett (2010) introduced phrases such as the ‘call of things’ and ‘thing power’ in her book Vibrant Matter. In an article in Eventual Aesthetics, she applies her thinking to some art objects that, now broken or dismantled, have been deemed a “total loss” by the insurance company. The items are the private property of artist Elka Krajewska, founder of the Salvage Art Institute. Krajewska invited Bennett and others to a dinner party to decide the future of these artworks. The discussion highlighted the realisation of the items being things that are and the guests being things that do, and the group struggled to “articulate an approach that didn’t see only humans as the locus of action. Here the idea was to attend to what the items might be doing to us.” She questioned whether there was a potential for a more horizontal interaction, “an engagement between bodies, some human some not, each of which would re-form the other and be re-formed as a result of the exposure” (Bennet, 2015:95).

In ‘Object relations in the museum: a psychosocial perspective’ Froggett and Trustrom discuss the views of psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas, who looks beyond the traditional object relation theory that is centred around our internal relationships with others (people or things), and investigates the intrinsic qualities of objects themselves. They quote Bollas as emphasising “that it is not just that we use objects, they, in a sense, use us”. And “we have an opportunity to negotiate with reality in order to gain experience of objects that release the self into being.” (Bollas 1992:42 cited in Froggett and Trustrom, 2014:494)

There are few times or places when something is not being asked of us, whether it’s to do more or buy more or be better, fitter or more productive. There is a stillness in a thing that is less “passivity and more vibratory tranquillity. The [object] has no desire to become otherwise than it is, and the human body plunges with it into a hiccup that suspends the progress of time and restlessness of desire. It becomes, for a moment, thrillingly content” (Bennet 2015:104). This idea of stillness, of finding some contentedness in the here and now seems to be an interesting and grounded starting place to explore the future. Allowing objects and our relationship with them to take us to an “existential dimension outside the process of cognition” is an exciting opportunity and exploration for everyone and especially artists (Froggett and Trustrom, 2014:494).

Bennett’s (2015) suggestion of the object drawing us into a “hiccup that suspends the progress of time and restlessness of desire” was what I was thinking about when I created a cast hug. I was interested in the idea of a vaguely familiar form that held a reminiscence of bodily interaction, perhaps evoked the memory of feeling, but held a ‘vibratory tranquillity’. The object asks nothing from you in a way that the intersubjectivity of a hug sometimes does. That moment of wordless recognition, outside of the cognitive process, perhaps what Bollas refers to as the ‘unthought known’, creates (I hope) that hiccup.

Fig. 4 Hug (2023)

These ideas may not have direct links to feminist theory, but they do challenge many areas of current day thought that have been discussed here and open up not only new ways of thinking but new ways of being, experiencing and living. New ways of coming back into our bodies through a resonance with something other, something that asks nothing from us.

Language and Women’s Embodied Writing

This connection with the body is referenced through language by Stark when looking at French feminist writing which “critique[s] rationality and the gendering of reason” (Stark, 2016:3). She quotes Cixous’ assertion that “writing is not neutral but is phallocentric and it elides the masculine nature by posing as universal (Stark, 2016:16). She says that women’s writing is different because it has the potential to emerge from the body and this “corporeality is fundamentally disruptive to masculine reason and order” (Stark, 2016;17). Stark surmises that these writers deploy their sexual difference in order “to challenge masculine systems of reason and rationality, reminding us that epistemology is not neutral” (Stark, 2016 :16).

Embodied writing or speaking is not straightforward as Susan Griffin explained when discussing how women struggled to tell the stories of what happened to their bodies as a result of rape. She says “the language is not available. What is here is old language with old connotations. Even the words soul and spirit have become so corrupted, so removed from immediate experience, mystified, used as mystification, as a way to alienate a being from herself” (Griffin 1986:51). In her work with survivors of rape and abuse, Griffin says “we were no longer ‘thinking’ in the way that Western man thinks, in the realm where thought is divided from feeling, and objectivity is imagined existing. We were discovering a different sense of clarity, one achieved through feeling” (Griffin, 1986:42-43).

What is conveyed here is a sense of struggle against the limits of thought and language to express bodily experience and knowledge and to make a re-connection back with the self.

The performance art of the 1970s sought alternative ways to tell stories for which there were no words. In referring to Ablutions, a performance piece by Judy Chicago and Suzanne Lacy, Elkin says, “The performance harnessed the power of repulsion to make its point, one they found could not be expressed in language alone” (Elkin, 2023:32).

But it is not just language that hinders women’s relationship with their bodies. Griffin talks about the difficulty of inhabiting – never mind embracing and loving – a body that has the potential to provoke violence: “Our bodies become things which we must hide. How does one move about the world in this body which has the power to invoke malevolence against oneself?” (Griffin, 1986:89). This is such a powerful point - not only do women live with the fear of potential violence and the trauma of actual violence, they also live with the alienation from a body that has the ability to incite violence. In Disobedient Bodies, Emma Dabiri. recognises this paradox: “The attention focused on our bodies is accompanied by a deeply-entrenched contempt for them and this is the result of specific cultural, philosophical and religious legacies” (Dabiri 2023:5).

How are women to overcome this bodily exile?

Homing

In The Man of Reason, Genevieve Lloyd (1993) discusses De Beauvoir’s statements that women have no myths of their own, that they still dream men’s dream and fail to set themselves up as subject. She talks about a ‘convivence in remaining ‘other’ to men, similar to Johnson’s suggestion of collaboration. “The internalisation of patriarchy has created a constriction of women’s thoughts, dreams, myths, language and reality which women need to break out of in order to transcend into a new future” (Lloyd, 1993:87).

Women’s myths and stories are lacking in the Christian West where our prevailing myth is that of Eve: created out of man, for man, in league with the devil and responsible for the sinfulness of humankind, man’s labour and women’s pain in childbirth. Definitely not a myth of our own. As Marine Warner points out, this is woman as subject matter in man’s story (The Great women Artists: Marina Warner on Eve, Lilith, Athena, Medusa, 2023). Other cultures with richer histories of storytelling do better. In Women Who Run with Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype, Clarissa Pinkola Estes suggests that fairy tales, myths and stories provide an understanding which “lead women deeper and more deeply still, into their own knowing. The tracks we all are following are those of the wild and innate instinctual self” (Estes, 2008:12). In the book she re-tells stories and myths from many different cultures and offers interpretations of the characters and meanings within them. Often the same tale is told in many different lands. In a chapter called ‘Homing, Returning to Oneself’, Estes tells the story of the Seal Maiden or Selke whose seal skin is stolen by a lonely fisherman who promises its return if the maiden will spend seven years with him. The story follows her agreement to do so, the birth of their child and her slow demise as the effects of her separation from her skin and the water become overwhelming. Estes expounds meaning from different elements of the story, most interestingly in this context, the idea of homing - returning to oneself, which she described as:

“The instinct to return, to go to the place we remember. It is the ability to find, whether in dark or in daylight, one’s home place. We all know how to return home. The exact answer to “Where is home?” is more complex... but in some way it is an internal place, a place somewhere in time rather than space, where a woman feels of one piece.”

Most crucially she goes on to describe home as:

“a place where a thought or a feeling can be sustained instead of being interrupted or torn away from us because something else is demanding our time and attention” (Estes, 2008:283).

This is an interesting point, and a resurgence of the idea that women need to be able to carve out space and time for themselves, and how difficult that is to achieve in the face of constant demands. These ideas were referenced by both De Beauvoir and Virginia Woolf. De Beauvoir calls these relational, social and cultural demands, ‘immanence’ or immersion in life. Her ideal for women was that they should break away from the ‘immanence’ in which they have been thus contained, to achieve their own transcendence - the state of self-definition and self-justification - through freely chosen ‘projects and exploits’ (Lloyd, 1993:100). These sounds very much like Bergson’s ‘free acts’.

Virginia Wolfe alludes to this experience in To the Lighthouse when describing Lily Briscoe’s inability to paint with Mr Ramsey wandering about the place: “’She could not paint.’ His very presence alters her vision: ‘She could not see the colour; she could not see the lines; even with his back turned to her, she could only think, But he’ll be down on me in a moment, demanding – something she felt she could not give him.’ She remembers from her youth what it is he’s after: her own ‘self-surrender” (Elkin, 2023:4).

Estes words help us to transcend. They offer us something recognisable, a place that we may not be able to get directions to, but which will know beyond doubt when we arrive. She is describing an intangible place that is only known through felt experience and an internal knowing. She explains further:

“Home is a sustained mood or sense that allows us to experience feelings not necessarily sustained in the mundane world: wonder, vision, peace, freedom from worry, freedom from demands, freedom from constant clacking. The physical place itself is not home; it is only the vehicle that rocks the ego to sleep so that we can go the rest of the way by ourselves (Estes, 2008:284).”

And:

“Home is the pristine instinctual life… where all is as it should be, where all the noises sound right and the light is good, and the smells make us feel calm rather than alarmed… Whatever revives balance is what is essential. That is home… There we can imagine the future” (Estes, 2008:284).

The language here is Mother Tongue. There is a reaching and yearning contained in the words; rationality and logic are nowhere to be seen. There is an identifiable longing if not experience that is immediately recognisable. A realisation of all that is lacking and that which is so hard to realise in the world today. A lacking that is full of potentiality.

Conclusion

This has been a tricky essay to navigate at times. While the terms Mother Tongue and Father Tongue could be seen as perpetuating the problematic power dynamic I am talking against, I have continued to use them as they exemplify the limitations of the language I am trying to counter and demonstrate Grosz’s suggestion that solutions have to co-exist with the problem. I am not suggesting we should co-exist with violence, but men and women do have to find a way to live together in peace and safety if not harmony!

Grosz points out that working out how men and women and can live together is a problem never solved, a problem lived alongside its solution. To deny the binary in this context seems futile, men’s violence against women is a binary issue, but there have to be more solutions that those we have been presented with so far. Disobediently refusing to engage with philosophies, realities and knowledges that undermine and perpetuate violence might be a start.

It should also be noted that women’s ability for refusal and disengagement will be unevenly effected depending on their lived experiences and the points I have made, and areas discussed are, I acknowledge, biased towards white, western, educated, affluent, cis gendered, non-disabled women, i.e., myself.

Although always saddened and distressed, I am never surprised when the news reports of more harassment, more rape, more violence, more death. While women are still ultimately believed to be less-than by the very structures that they are seeking to change, I have minimal hope for change from that direction. This does not mean we should give up hope but need to look for it elsewhere, perhaps as Solnit suggest, in uncertainty, or spaces of not-knowing; or to investigate new materialites for alternative knowledges and explore our interaction with objects as a route into a contented silence, beyond the realms of cognition, that might allow for transcendence.

It is ironic and terribly sad, to think about women’s exile from their bodies, and then realise that perhaps the way out of patriarchy is to return into them, to re-discover the wisdom and knowledge that reside there. Wouldn’t it make sense that the war that has been raged against women’s bodies through objectification, sexualisation, rape, violence and death has been because the end to patriarchy is housed within them.

As Griffin writes: “may be the reason, finally, that our very selfish motion, to heal ourselves, to tend to our own wounds, may turn out to be the most radical motion of all, one that heals not only ourselves but eventually all, and thus transforms the social order absolutely” (Griffin, 1986:53).

Bibliography

Bennett, J. (2010) Vibrant Matter Duke University Press: North Carolina. USA.

Bennett, J. (2015) ‘Encounters with an Art Thing’ In Evental Aesthetics 3 (3) pp. 71-87. Available at: http://salvageartinstitute.org/janebennett_encounterswiththesartthing.pdf IAccessed 15/10/2023).

Bollas, C. (1992) Being a Character: Psychoanalysis and Self Experience. East Sussex: Routledge.

Bruiger, D. (2019) Art and the Unknown. Available at: https://philarchive.org/archive/BRUAAT-7 Accessed on 12/11/2023.

Cocker, E. (2013) ‘Tactics for Not Knowing’ In: Fortnum, R and Fisher, E eds., On not knowing: how artists think. Black Dog Publishing: London.

Cole, H. and Pillay, A. (2021) VOICE'S 24-HOUR TRUCE SERIES: Volume1 Available at: https://voiceamplified.org/truce-volume-i/ (Accessed 18/10/2023).

Dabiri, E. ( 2023) Disobedient Bodies Wellcome Collection: London.

MITPress (2019) I Want a Twenty-Four-Hour Truce During Which There Is No Rape: An Excerpt from ‘Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin’

Available at :

https://mitpress.mit.edu/i-want-a-twenty-four-hour-truce-during-which-there-is-no-rape-an-excerpt-from-last-days-at-hot-slit-the-radical-feminism-of-andrea-dworkin/ Accessed (15 December 2023).

Elkin, L. (2023) Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art Chatto and Windus: London.

Estes, C.P. (2008) Women Who Run With The Wolves: Contacting the Power of the Wild Woman. 1st edn. Rider: Sydney.

Froggett, L and Trustram, M. (2014) ‘Object relations in the museum: a psychosocial perspective’, In Museum Management and Curatorship 29 (5), pp. 482-49. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264540240_Object_Relations_in_the_Museum_a_psychosocial_perspective (Accessed January 4 2024).

FTW 2007 Elizabeth grosz.mov (2007)[YoutubeVideo]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mwHoswjw5yo (Accessed 4 January 2024).

Gilligan, C. (1993) In a Different Voice Harvard University Press: Massachusetts.

Graham, D.L. (1994) Loving to Survive New York University Press: New York.

Griffin, S. (1986)- Rape: The Politics of Consiousness. Harper & Row Publishers: New York.

Griffin S. (1978) Women and Nature. Harper & Row: New York.

Going Farther Out of Our Minds Part 1. [2016] [YouTubeVideo]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VGDfCQmKuPA (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Grosz, E. (19950 ‘Sexual Difference and the Problem of Essentialism’, In Grosz, E Space, Time and Perversion Routledge: New York Chapter 3

Grosz, E. (2011) Becoming Undone:Darwinian Reflection on Life, Politics and Art. Duke University Press: North Carolina, USA.

Grosz, E. (2010a) ‘Feminism, Materialism and Freedom’, In Coole, D. et al. (eds) New Materialisms : Ontology, Agency, and Politics. Duke University Press: New York pp. 139–157.

Grosz, E. (2010b) ‘The Future of Feminist Theory: Dreams for New Knowledges’ In: Revista Eco-Pos, 13, (3). pp 38-52. Available at: https://revistaecopos.eco.ufrj.br/eco_pos/article/download/848/788/1649 (Accessed 21 September 2023).

Grosz, E. (2010c) ‘The Practice of Feminist Theory’ In: Difference: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 21(1) pp. 94–108. Available at : https://read.dukeupress.edu/differences/article/21/1/94/97692/The-Practice-of-Feminist-Theory (Accessed 2 January 2024) .

Hubbard, R. (1988) 'Science, Facts, and Feminism' In: Hypatia 3 (1) pp.5–17. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/3810048 (Accessed on 20 October 2023)

Le Guin, U. (1989) Dancing at the Edge of the World. Grove Press: New York.

Lippard, L. (1995) The Pink Glass Swan. The New Press: New York.

Lloyd, G. (1993) Man of Reason. Routledge: London.

Lorde, A. (2018) The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. Penguin Classics: London.

Johnson, S. (1987) Going Out of Our Minds: The Metaphysics of Liberation The Crossing Press: California.

Malafouris, L. & Renfrew, C. (2013) How Things Shape the Mind : A Theory of Material Engagement. MIT Press: Massachusetts.

Millett, K. (2000) Sexual Politics University of Illinois Press: Chicago.

Sjoo, M. & Mor, B. (1987) The Great Cosmic Mother Harper One: New York.

Solnit, R. (2016) Hope in the Dark Canongate Books: Edinburgh.

Solnit, R. (2017) The Mother of All Questions. Granta Books: London.

Stark, H. (2016) Feminist Theory After Deleuze (Deleuze and Guattari Encounters). Bloomsbury Academic: London.

The Great Women Artists: Marina Warner on Eve, Lilith, Athena, Medusa (2023) At: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/marina-warner-on-eve-lilith-athena-medusa/id1480259187?i=1000633283650 (Accessed 04/11/2023).

UNwomen.org (s.d.) At: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Womanhouse (1972) [YoutubeVideo]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xx0ZPfLrsfk (Accessed 15 November 2023).

List of Illustrations

Fig 1 Lacy, S. (1977) Three Weeks in May [Photograph] at: https://www.suzannelacy.com/three-weeks-in-may (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Fig 2 Lacy, S. (1977) Three Weeks in May [Photograph] at: https://www.againstviolence.art/twim-rape-maps (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Fig 3 Chicago, J. and Shapiro, M. (1977) Womanhouse [Photograph] at: https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/judy-chicago-womanhouse (Accessed 20 November 2023.)

Fig 4 Chicago, J. (1972) Menstruation Bathroom (Photograph] at https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-revisiting-famed-feminist-exhibition-womanhouse-intersectional-lens (Accessed 10 January 2024).

Fig 5 Holy, N. (2023) Hug [Plaster] In possession of: the author: Kent.

[1] It is worth noting that Graham gives over a section of her introduction to explain that “this theory is being presented for the first time and despite the fact that an enormous amount of research in the literature supports it, it is an empirically untested theory” (Graham 1994 p.xviii), but one which she hopes will encourage research to test the theory and provide new knowledge as well as to help women find ways to improve their situation. Part of the reason for including this work is to acknowledge its importance to allow space for such research to move from the margins into the ‘acceptable’ mainstream.